|

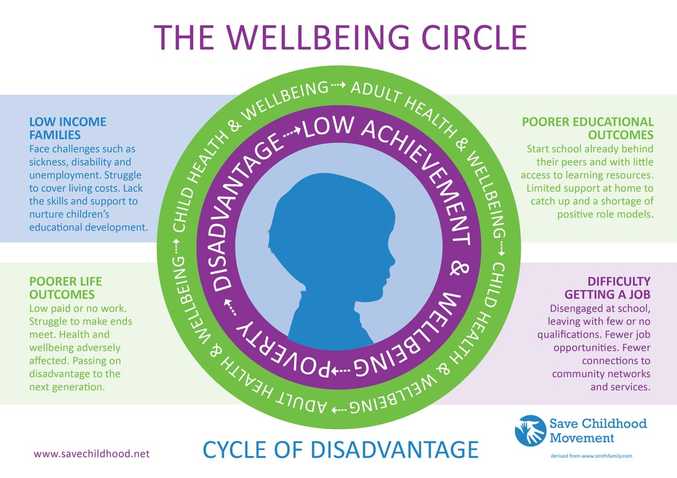

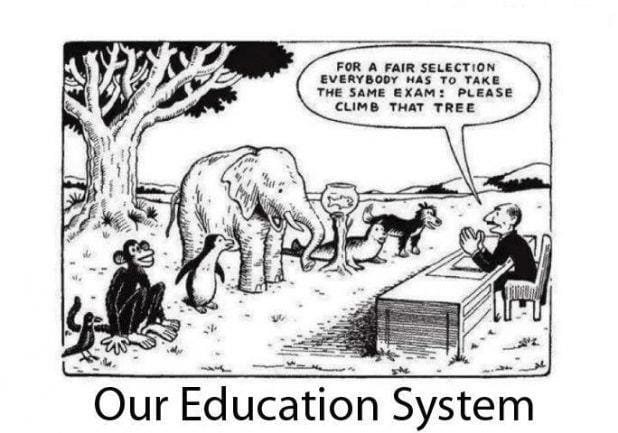

As the year is drawing towards its end I have been thinking about why I do what I do, when so often it seems like we are faced with insurmountable barriers from systems that seem to be determined to maintain old and decaying structures, rather than welcoming in the new. People around the world are clearly demonstrating that they are tired of the old ways of doing things, and particularly so when these are damaging to their children, parents and communities. Too many of us have been made to feel that the only things that give us value are personal achievement (within very limited boundaries), money and things, whereas it is clear that what really underpins a happy and contented life is relationship, personal meaning and contribution. There is nothing wrong with money, and of course countries need to be economically sustainable, but in some countries it seems that a terrible human cost is currently being paid, particularly in the lives of young children. We know that the foundations of healthy societies are laid in the early years. In fact Professor Heckman and his colleagues at the University of Chicago have just released new research that suggests a 13% Return On Investment through early childhood programs, a substantial increase from the 7 - 10% that is most often quoted. What that means is that every country should be prioritising the health and wellbeing of its youngest citizens,not only because this creates happier and healthier societies, but because it is an economic necessity. Poor levels of attachment and early nurture have a devastating and hugely costly impact on society. We also know from numerous studies (but it is also obvious) that the most influential relationship in a child's life is the one with his or her parents, and particularly the mother. Above all young children need love and security - and what is less often mentioned, time - time to simply be together with no obvious agenda, time for silliness and play, and time for the deep connections that we crave as highly social animals. It's not just children that need time to be with their parents, but that parents need to be nurtured by the freedom, wonder and playfulness of being with their children. The next best thing to a parent is a loving, caring and emotionally mature adult - so grandparents and close relatives are really important, as are other first carers, along with childminders and early years practitioners. The common element for countries that do well on both achievement and wellbeing indices is that they have invested heavily in family and community life - recognising that cycles of poverty and social exclusion being passed down from one generation to the next can only be broken by appropriate levels of state support. They have also recognised that the people working with the youngest children need to be the most qualified and valued - and not the least. In many Scandinavian countries a large percentage of the early years workforce have degree and masters level qualifications in recognition of this fact. And in Italy the remarkable Loris Malaguzzi created his own dedicated early years training, calling on young children to be recognised as the holders of important human rights, who learn and grow through relationship with others. In the future our children are going to have to compete within a global market - and it is not just academic qualifications that they will be measured on, but also their social skills, resilience, empathy, character and how much they listen to and care for others. All of these skills are formed in early childhood and by providing diminished environments we are robbing children of their true potential and their ability to move beyond the social barriers of class and disadvantage. What does the situation in England tell us about the current government's commitment to children and families?

It has only been in the last few years that I have become more actively focused on how policies get made in England and it has been a pretty depressing process. The evidence clearly suggests that policymakers tend to be interested only in evidence that fits their own need, ideology or prejudice, and they may ignore or even abuse those who provide evidence that doesn't fit the political bill. I personally experienced this in 2013 when the Save Childhood Movement first launched the Too Much Too Soon Campaign and the concerns of 127 eminent experts, including 17 Emeritus Professors, were summarily dismissed as belonging to the 'Blob'. This was similar to the DfE response to Robin Alexander's rigorously evidenced and potentially ground-breaking Cambridge Primary Review, which provided a damning critique of the impact of current policy on schools and children, but also offered a number of carefully thought-through solutions. Instead of giving these the time and attention that they deserved, the DfE then implemented the Rose Review and you can make your own minds up re the qualitative difference between the two by looking at this CPR analysis (which can now interestingly be found on a government website). Since then we have seen a succession of expert consultations take place, but these of course mean nothing if the recommendations are then ignored (with seemingly no rigorous evidence-base) by those in power and an example of this was the 2014 Nutbrown Review that resulted in Cathy Nutbrown issuing this response to the DfE. A Primary Assessment Inquiry is currently underway, but I find it deeply frustrating that these processes are continually repeated when so much good work has already been done. This endless re-inventing of the wheel takes up a great deal of time and resources and seems to do little more than provide an excuse that government is responding to expert concerns without actually having to do anything about them. I was one of the signatories for this Guardian letter, that was published on Christmas Day, but I fear that without us chaining ourselves to the railings, no-one is really taking any notice. Despite considerable evidence suggesting the opposite, successive governments have invested in the naive belief that early learning can be forced, that raising test scores in literacy and numeracy will elevate the country’s economic performance, and that copying successful nations’ educational policies will raise standards to an acceptable level. Not only that, but they are increasingly influenced by the media. As Robin Alexander started in his essay 'Moral Panic' "In many countries, including the UK, the potential of international student achievement surveys such as TIMSS and PISA is being subverted by political and media fixation on the resulting league tables. These prompt not just well-founded efforts to learn from others’ success but also ill-founded assertions about educational cause and effect, inappropriate transplanting of the policies to which success is attributed, and even the reconfiguring of entire national curricula to respond less to national culture, values and needs than to the dubious claims of ‘international benchmarking’ and ‘world class’ educational standards – the latter equated with test scores in a limited spectrum of human learning." To add to the dilemma, Early Years and Education Ministers (most of whom have no prior knowledge of the field) constanty come and go, everyone is focused on short-term wins, rather than long-term vision - and children, parents and schools are at the mercy of constantly changing agendas. I read in a report somewhere (that I am still trying to track down) that over the last two decades an 18 year old in Britain will have experienced more than 400 changes in education policy and that currently doesn't seem like an exaggeration.

I have no doubt that most people involved in government are well-intentioned and genuinely trying to do their best. It has become clear, however, that the current system simply isn't serving the true needs of the people within it. Deep and lasting improvements can surely only be achieved when those in power have the courage and vision to put the best interests of children and families at the heart of political policymaking. When you look at the findings of James Heckman, can we really afford not to?

3 Comments

Kate Johnston

12/31/2016 10:07:41 am

Thank you for this thoughtful response to what is happening in educationand the political response to it!

Reply

Claire Morley

1/8/2017 08:02:49 pm

Hear hear. I would like to see the education department (and several others too) taken out of the reach of politicians who as you say mostly come from an ideological position or simply one perceived as vote-winning/supported by the media. Our national institutions should be run according to the evidence of what works best and , as you say, there is plenty of it already on the shelf.

Reply

Edwina Mitchell

2/27/2017 04:14:32 am

I totally agree with what you say and shudder to think what government policies are doing to the future health and well being of our young children. Eventually society will pay the price for expecting too much too soon and not supporting parents to have sufficient time at home with their babies

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorWendy Ellyatt ArchivesCategories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed