|

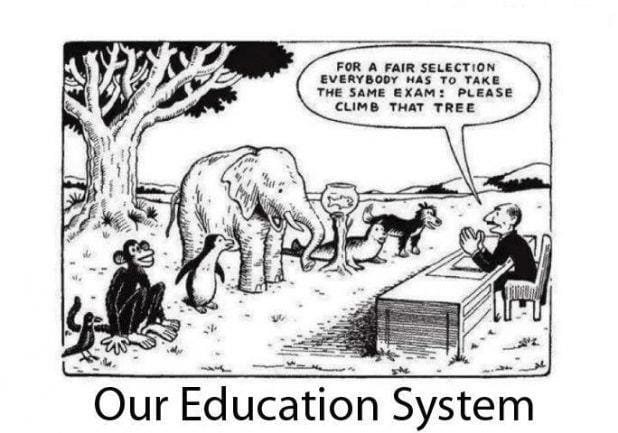

I suspect lots of people might think I'm crazy to commit the Save Childhood Movement to an event as big as the 2017 International Festival of Childhood. Over four days we are bringing together an extraordinary gathering of speakers to talk about what's going on in the lives of young children and how we can create a more caring and meaningful world. We have committed to two major venues, with all the staging and promotional costs of putting on a top-notch event. Not only that but we are working with a wonderful creative partner in Bath who is overseeing an extravaganza of playful external events and activities - all of which will be free. So we will have what we hope will be an internationally important conference embedded within a city-wide celebration of childhood. The movement is not a large organisation, supported by major sponsors or members of the national media. Instead it's a young and totally voluntary organisation that, other than two small national lottery grants that it was awarded for the development of National Children's Day UK, has been pretty much self-funded. In the three years since its launch people have freely given what has amounted to thousands of hours of voluntary time and expertise, but we still rely on a tiny core team. Any funds that we raise this year will go to ensuring that we can grow our team and its activities in a solid and sustainable way. Each topic that we are covering in the festival subsequently deserves a conference of its own and, if it is successful, this is something that we plan to help happen. We also want to initiate a series of national conversations about the kind of values we really want to see in society. My own feeling is that big problems demand big solutions and one of the issues with current political leadership is that it focuses only on the short-term, rather than inspiring people to come together to re-write the rules and shape a better and more compassionate future. We have to start somewhere and thinking small simply isn't going to hack it. This morning I read Sian Griffiths' Sunday Times review of Michele Hutchison and Rina Mae Acosta's book 'The Happiest Kids in the World'. The book documents Michele's experience of moving from the UK to bring up her children in Amsterdam and the huge gulf between the pressurised, competitive way she was brought up and the Dutch parenting style. "In Holland family life is fiercely valued. Instead of a culture of long office hours, it is a matter of national pride to leave work early to spend time with your children...There is no exam pressure for under tens or homework in primary schools. Instead the importance of having friends and building social skills is emaphasized." "Childhood over here consists of freedom, plenty of play and little academic stress...In contrast we see British parents feeling constantly challenged and unsettled by their own unrealistic expectations and by other people's opinions... Parents in the UK put kids under immense pressure to succeed and be perfect." I resonate with this because it took me years to throw off the 'having to be perfect' burden of my own British up-bringing. I was terrified of failure and the result was that I held back from doing the things that I really felt drawn to and speaking up about the things that I cared about. It is only in my later years that I have realised that I am more terrified of coming to the end of my days without having tried - and that what matters for all of us is that we can become the best versions of ourselves. Nature has not designed us all to be the same, for the very good reason that human communities only work when there is a rich and varied profusion of interests, talents and capabilities that cover all the aspects that make things work. We need people that are great with their hands and can take things apart and put them together again. We need carpenters and electricians and builders and plumbers and gardeners. We need thinkers, explorers, innovators and and scientists. We need artists and writers, musicians and healers. We need people that lead and people that are happy being led. What we don't need is a world where, from the youngest age, children are separated from their natural instincts as exhuberant lifelong learners and where people are made to feel that they only have value and worth within a very limited range of human capacities,. That is what we are trying to say through the festival - that human beings are extraordinary, diverse, multi-talented and complex creatures - each one of us totally unique and capable of whatever has richness and meaning for us as individuals. But we are also innately social beings that understand ourselves and grow through our relationship with others. Somehow we have allowed systems to be created that have failed to acknowledge this, that have made us fear judgment and failure more than not being who we really are, and that have made success all about qualifications and things, rather than fulfillment and worth. Outer wealth has come at the cost of inner wealth - and that is too high a price to pay.

We want every child to feel valued and special and that can only come about if we are brave enough to question all the old systems through the lens of child, family and community wellbeing. That is what the festival is about and is why I hope you will support us at the event and become part of the solution. Hopefully this is just the beginning of us working together to bring in the new... You can see the festival website on www.festivalofchildhood.com - and we are now also on Twitter

0 Comments

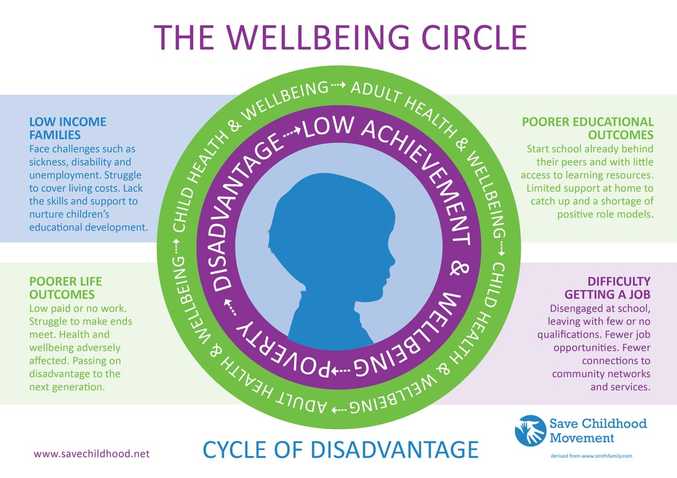

As the year is drawing towards its end I have been thinking about why I do what I do, when so often it seems like we are faced with insurmountable barriers from systems that seem to be determined to maintain old and decaying structures, rather than welcoming in the new. People around the world are clearly demonstrating that they are tired of the old ways of doing things, and particularly so when these are damaging to their children, parents and communities. Too many of us have been made to feel that the only things that give us value are personal achievement (within very limited boundaries), money and things, whereas it is clear that what really underpins a happy and contented life is relationship, personal meaning and contribution. There is nothing wrong with money, and of course countries need to be economically sustainable, but in some countries it seems that a terrible human cost is currently being paid, particularly in the lives of young children. We know that the foundations of healthy societies are laid in the early years. In fact Professor Heckman and his colleagues at the University of Chicago have just released new research that suggests a 13% Return On Investment through early childhood programs, a substantial increase from the 7 - 10% that is most often quoted. What that means is that every country should be prioritising the health and wellbeing of its youngest citizens,not only because this creates happier and healthier societies, but because it is an economic necessity. Poor levels of attachment and early nurture have a devastating and hugely costly impact on society. We also know from numerous studies (but it is also obvious) that the most influential relationship in a child's life is the one with his or her parents, and particularly the mother. Above all young children need love and security - and what is less often mentioned, time - time to simply be together with no obvious agenda, time for silliness and play, and time for the deep connections that we crave as highly social animals. It's not just children that need time to be with their parents, but that parents need to be nurtured by the freedom, wonder and playfulness of being with their children. The next best thing to a parent is a loving, caring and emotionally mature adult - so grandparents and close relatives are really important, as are other first carers, along with childminders and early years practitioners. The common element for countries that do well on both achievement and wellbeing indices is that they have invested heavily in family and community life - recognising that cycles of poverty and social exclusion being passed down from one generation to the next can only be broken by appropriate levels of state support. They have also recognised that the people working with the youngest children need to be the most qualified and valued - and not the least. In many Scandinavian countries a large percentage of the early years workforce have degree and masters level qualifications in recognition of this fact. And in Italy the remarkable Loris Malaguzzi created his own dedicated early years training, calling on young children to be recognised as the holders of important human rights, who learn and grow through relationship with others. In the future our children are going to have to compete within a global market - and it is not just academic qualifications that they will be measured on, but also their social skills, resilience, empathy, character and how much they listen to and care for others. All of these skills are formed in early childhood and by providing diminished environments we are robbing children of their true potential and their ability to move beyond the social barriers of class and disadvantage. What does the situation in England tell us about the current government's commitment to children and families?

It has only been in the last few years that I have become more actively focused on how policies get made in England and it has been a pretty depressing process. The evidence clearly suggests that policymakers tend to be interested only in evidence that fits their own need, ideology or prejudice, and they may ignore or even abuse those who provide evidence that doesn't fit the political bill. I personally experienced this in 2013 when the Save Childhood Movement first launched the Too Much Too Soon Campaign and the concerns of 127 eminent experts, including 17 Emeritus Professors, were summarily dismissed as belonging to the 'Blob'. This was similar to the DfE response to Robin Alexander's rigorously evidenced and potentially ground-breaking Cambridge Primary Review, which provided a damning critique of the impact of current policy on schools and children, but also offered a number of carefully thought-through solutions. Instead of giving these the time and attention that they deserved, the DfE then implemented the Rose Review and you can make your own minds up re the qualitative difference between the two by looking at this CPR analysis (which can now interestingly be found on a government website). Since then we have seen a succession of expert consultations take place, but these of course mean nothing if the recommendations are then ignored (with seemingly no rigorous evidence-base) by those in power and an example of this was the 2014 Nutbrown Review that resulted in Cathy Nutbrown issuing this response to the DfE. A Primary Assessment Inquiry is currently underway, but I find it deeply frustrating that these processes are continually repeated when so much good work has already been done. This endless re-inventing of the wheel takes up a great deal of time and resources and seems to do little more than provide an excuse that government is responding to expert concerns without actually having to do anything about them. I was one of the signatories for this Guardian letter, that was published on Christmas Day, but I fear that without us chaining ourselves to the railings, no-one is really taking any notice. Despite considerable evidence suggesting the opposite, successive governments have invested in the naive belief that early learning can be forced, that raising test scores in literacy and numeracy will elevate the country’s economic performance, and that copying successful nations’ educational policies will raise standards to an acceptable level. Not only that, but they are increasingly influenced by the media. As Robin Alexander started in his essay 'Moral Panic' "In many countries, including the UK, the potential of international student achievement surveys such as TIMSS and PISA is being subverted by political and media fixation on the resulting league tables. These prompt not just well-founded efforts to learn from others’ success but also ill-founded assertions about educational cause and effect, inappropriate transplanting of the policies to which success is attributed, and even the reconfiguring of entire national curricula to respond less to national culture, values and needs than to the dubious claims of ‘international benchmarking’ and ‘world class’ educational standards – the latter equated with test scores in a limited spectrum of human learning." To add to the dilemma, Early Years and Education Ministers (most of whom have no prior knowledge of the field) constanty come and go, everyone is focused on short-term wins, rather than long-term vision - and children, parents and schools are at the mercy of constantly changing agendas. I read in a report somewhere (that I am still trying to track down) that over the last two decades an 18 year old in Britain will have experienced more than 400 changes in education policy and that currently doesn't seem like an exaggeration.

I have no doubt that most people involved in government are well-intentioned and genuinely trying to do their best. It has become clear, however, that the current system simply isn't serving the true needs of the people within it. Deep and lasting improvements can surely only be achieved when those in power have the courage and vision to put the best interests of children and families at the heart of political policymaking. When you look at the findings of James Heckman, can we really afford not to? |

AuthorWendy Ellyatt ArchivesCategories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed